Before you begin writing, you may want to focus on your list of ideas. Ideas you may have decided are excellent topics. In fact, some of those ideas may serve as shorthand reminders regarding incidents you’re certain are worth developing into a short story or a novel.

As excited as you are about beginning, you’ve taken my advice to create a brief outline. Even if it’s just a few lines, it will serve as a platform, a foundation for your work.

That’s why, when you’ve finally begun to type your exciting first sentence (you know it will be exciting because I’ve suggested that your first sentence must grab your readers to hold their attention), you may be struck by a concern for the people who comprise your closest circle of friends.

Since your story may include a number of them, you begin to wonder whether any of them may be offended by your version of the truth you want to share. That concern rightfully haunts you.

Should you tell them what you plan to write before you begin? Ask their permission? Get them to sign an agreement that they won’t sue you?

As a result of such considerations, your fingers, having been ready to dance on your computer’s keys, feel leaden. You imagine the ‘true story’ articles your local newspaper might publish about what you’ve written. You worry that those articles may provide even more details than you ever wanted to share.

Considering that, you stop and stare into your nearby mirror. What if one of your subjects decides to reciprocate by writing their version — about you?

That may be a viable concern, especially if you don’t have documented proof of all of your claims. Even if you find old photos taken at the time of the incident, those images may not offer much protection.

That’s why you may want to consider dispensing with a tell-all novel and, instead, compose a completely fictitious set of characters who live in a city you’ve created that has only a passing resemblance to your own. As for your ‘new’ characters who resemble real people, you may want to give them a different sex than that of the ones who inspired you.

Once you have a workable list of characters, you’ll find it’s easier to create a city — or country — where the characters reside. Only then should you focus on writing your all-important first sentence, perhaps one of the most important in your book.

Often that sentence is described as the hook that catches your readers’ attention. Rather than try to prescribe such a sentence, I’ll suggest you locate a few of your favorite books. In each of them, read the first sentence, the first paragraph, and the first page.

Take notes about what each of those ‘firsts’ have in common. Write about what you enjoyed about each one.

Once you’ve completed those notes, laminate them! Keep that well-preserved lamination near your computer. Refer to it often. Use it to assist you as you start your book, determine its direction and pace.

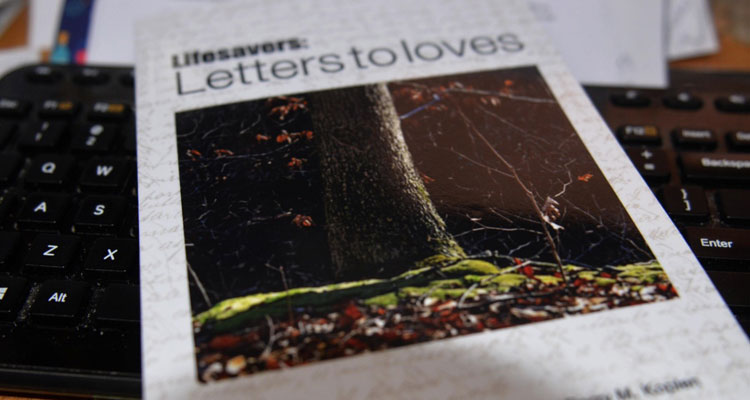

If you’d like, you may want to read the first page of my first LIFESAVERS book, Letters to loves. Below is a picture of its cover. I’ll end this piece with its first two sentences and my final note of encouragement: enjoy every page you write, whether it’s fact or fiction!

Just because she knew how to sew didn’t make her special. To look at her, most would think Piri was a model others might sew for…