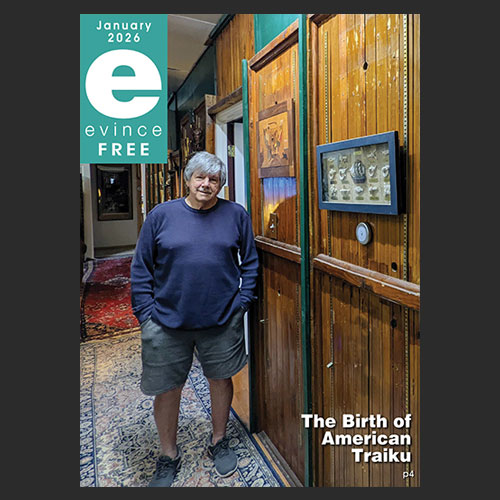

Nate Hester is living his dream. The visual artist, whose work explores the rich tapestry of American landscapes and the dynamics of modern home life, has found an unlikely muse in Danville, a city whose layers of history, texture, and everyday beauty have become integral to his artistic vision.

From Deep-Fat Frying to Fine Art

Hester’s path to becoming a full-time artist wasn’t linear. “I have been drawing my entire life,” he says. But along the way, he’s worn many hats: deep-fat fried seafood short-order cook, Methodist pastor and hospital chaplain, cybersecurity sales executive, educator, and college professor. “Through a mid-life crisis and some strokes of good luck, I now have my dream job and get to do what I love all day every day,” he reflects. “I draw and make stuff full-time!”

His connection to Danville runs deep. Hester’s father was born here and grew up in Turbeville and Chatham. His grandmother earned her teaching certificate from Averett. His life partner was born in Danville, graduated from George Washington High School before earning a medical degree and returning to practice obstetrics in the city. Their daughter’s first home was on Paxton Street at the edge of the Old West End.

Southern Hospitality as Artistic Philosophy

Danville has profoundly shaped Hester’s approach to art making. “Danville is a place for everybody,” he explains. “It is a place where ordinary folks are living good and decent lives by loving each other in quiet and extraordinary ways—over sharing with each other in good-natured fun in the Food Lion check-out line, for example.”

This sensibility infuses his work. “I want to be a visual storyteller that always connects to our shared common human experience,” Hester says. “I want people to be able to see a recognizable face or toy figurine or flower arrangement when they look at my work. I do not want folks to feel lost. I do not like it when art makes someone feel dumb.” He describes this approach as “a form of Southern hospitality,” a deliberate rejection of “the elitism, coldness and meanness of portions of the New York art scene.”

Danville’s complex history also resonates in his work. As an advocate for racial justice and reconciliation, the fact that Danville was the last Capitol of the Confederacy holds deep significance. He’s currently working on a creative response to this legacy with historian Berkely Pritchett at the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History.

Textures of Place, Layers of History

“I love the textures of this place,” Hester says, listing the brick warehouses in the River District, the cobblestone streets, the river running over rocks, the hills, the mansions, “the glitz of the casino, the shimmering lights of the strip mall and fast-food restaurants on Piney Forest and the churches.” He wants his artwork to serve as “time capsules in this way—holding good and bad memories—repositories of our hopes and fears—a little like an antique mall.”

The city’s economic narrative—cycles of boom and bust, glory and decline and renewal—mirrors in his materials. “I guess that Danville has inspired me to use materials that are elegant alongside materials that might have been discarded or considered unimportant,” he reflects. “We were once an important destination… then, we were a bit forgotten about for a few decades when the mills closed and now, we are on the rise again. I think that my drawings reflect the refinement and roughness of Danville.”

The Love Letters Series

This philosophy manifested in his “Love Letters” series of over 100 drawings, which began during his time teaching at Averett University. “One Saturday morning, I ran from campus all the way out to the airport and back,” he recalls. “Along the way, I picked up trash along 58 East towards South Boston—like a crow might gather bits of plastic to waterproof its nest. When I got back, I started sewing those found objects into the giant roll of paper that I was working on.” That piece, eventually titled “Bad Boy,” became the first in the entire series.

Danville has also reconnected Hester with his love of crafts. Growing up attending the Cedar Grove Quilt Show with his grandmother in Orange County, North Carolina every April, he developed an appreciation for regional craft traditions. “I love how regional towns in the South still love pottery and wood carving and sewing and quilting and crocheting,” he says. “Since my time in Danville, I have really worked to reincorporate my crafting into my fine art. Without a doubt, this place influences what I do and how I do it.”

A Creative Process Like Fishing

When asked about his choice of media—which ranges from collage and found objects to ceramics and large-scale installations—Hester shares a story about fishing with his grandfather. After helping young Nate get started, his grandfather would move to his own spot, often right before sundown. “Every cast would bring in a giant fish—catfish, bass, crappie—you name it, one after the next. He never said how he did it. He just did it. I have absolutely no idea how I use the materials I use. I just do.”

His creative process is labor intensive. “Some artists work with a sort of aristocratic panache; they can just walk up to a canvas and with effortless ease, breathe beauty onto it. That’s not me. I am a grinder,” he admits. “I have to get down in the trenches and roll up my sleeves and work and work and work. I am from a tobacco-farming family after all.”

For Hester, the most powerful art has an element of wildness to it. “I love art the most when being in front of it is like running into a wild animal in the woods by yourself at night… You catch the eyes of a fox or bear. For a brief second, you have a sense of terror; you wonder if you could be killed. You are aware that something else is alive and that you want to stay alive. I don’t want my work to scare necessarily, but I want it to be as wild and free and arresting as a living thing.”

His process follows a cycle of transformation. “I start with a great idea. I summon all my positive energy and head out on the adventure of achieving that vision. It ends in ruin. The great idea dies. I am miserable. But in the doldrums, in the middle of the ocean with no wind, a breeze hits the sails, and you set off in a new direction. Birth. Death. Resurrection. That’s my process.”

Rooted in Community

Hester’s daily life in Danville is woven into the fabric of the community. He’s a member of Vance Street Missionary Baptist Church, attends Patricia Hall’s African Dance class on Monday nights, goes to Planet Fitness before sunrise each day, and frequents shows at the North Theater and Carrington Pavilion. He jogs along the Dan River, gets ice cream at Bubba’s, walks past Doyle Thomas Park, and occasionally buys a lottery ticket when the Powerball exceeds a billion dollars.

“Have you been in?” he asks about his studio space, which he describes as “literally THE BEST office to come to work in every day.” The owner, Rick Barker, has outfitted it with floor-to-ceiling windows and exposed red brick walls. “It means the world to me to be part of this community. I truly hope that things work out for us to remain in town our whole lives.”

Harmony in the Modern Home

Hester describes himself as a landscape painter, but his landscapes are interior ones. “I have been thinking a lot lately about the landscape of the modern American home,” he explains. “I have been wondering how technology has changed how we live together under a single roof. I think about how different things were for my grandparents’ generation. I think about the progress that we have made and the things that we have lost along the way.”

“In my work, part of the thrill is to put things together that otherwise should not go together and to see if I can make the various elements sing. Harmony is important in a home.” Children particularly respond to his work, he notes, loving to find recognizable elements—”like if one of the heads of an imaginary avatar is Shrek or Plankton… Donald Duck or Harry Potter.”

Highbrow and Down-Home

Balancing local community connection with global art-world ambitions comes naturally to Hester. “Do you like looking at the clouds in the sky and trying to name the shapes they take?” he asks. “Like a certain poof, it looks all the world like a dragon chasing a chicken. Well, I do, too. One of the ways that I keep it down-home is with my titles. Like one of the ‘Big Bandage’ sculptures is called ‘He Shot Himself in the Foot with a Bottle Rocket at the Cookout Last July 4th.’ Highbrow and down-home; that’s my vibe.”

Looking Ahead

Having spent a year traveling to art residencies in New Orleans, New York City, France, and Japan, Hester is now back in Danville with ambitious plans. He’s excited about making giant, automated pop-up books, learning to use a rug tufting gun, and creating totems from downed trees donated by David Dwyer at Danville Tree Care.

In 2026, he’ll be working with Radar Curatorial to mount a show at Apex Arts in Brooklyn, New York, and with Diana Mayer at Spring/Break Art Fair. But perhaps the most meaningful project on his horizon is the one he’s developing with Berkely Pritchett, involving the legacy of the Sutherlin Plantation.

“It is an exciting time in my studio life and career trajectory,” Hester reflects. And through it all, Danville remains not just his home base, but his inspiration—a place where the textures of everyday life, the weight of history, and the warmth of community converge to create something beautiful and true.

Note: Nate Hester would like to give credit to John Scollo at the Danville Museum of Fine Arts & History for teaching a ceramics class. He has loved exploring that medium.